Business owner Jeffery Capazzi has seen Long Island’s opioid crisis up close among his workers.

“We had certain people being sent to rehab,” said Capazzi, president of the Jobin Organization, a Hauppauge construction company that makes and installs exterior wall systems. “We’ve had people that we’ve lost through overdoses.”

Greg Demetriou, president and chief executive of marketing company Lorraine Gregory Communications in Edgewood, said he and his staff were devastated when the granddaughter of a worker died of an overdose last year. A childhood friend of one of the company’s graphic designers also died of an overdose last year.

“When such news is received it puts a heaviness in the air,” Demetriou said. “Even those not directly affected feel devastated for their co-workers.”

The opioid crisis is taking a toll on Long Island’s companies, executives and experts say. Companies that have lost workers to the epidemic face the daunting tasks of comforting a traumatized workforce. They also deal with the reduced productivity of addicted workers or employees whose loved ones are addicted. And they and their employees struggle with the stigma of drug addiction, which experts say stifles open communication about the problem.

A U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report last year said that employees in their prime working years, ages 25 to 54, had the highest rates of drug overdose deaths in 2016. Overdose deaths began climbing, as people addicted to prescription opioids started feeding their habits with illegal opioid derivatives like heroin and fentanyl, the potent synthetic opioid that has become a popular component in the sales of illicit street drugs, the report said.

In fact, 70 percent of people with a substance abuse disorder are in the workforce, said the National Safety Council, based in Itasca, Illinois.

The White House Council of Economic Advisers last year estimated that the opioid crisis cost the U.S. economy $504 billion, or 2.8 percent of the total value of goods and services produced in this country in 2015.

Statewide, 54 percent of New York residents said they have been touched by the opioid epidemic because of a family member or colleague who has abused opioids, according to a recent Siena College poll, a result the researchers called “shocking.”

And Long Island has been hit hard as well. Law enforcement and medical examiner officials estimate that 600 people on the Island died last year from overdoses, up from the previous record high of 555 in 2016.

“Many employers I work with are struggling with the workplace impacts of opioid addiction,” attorney Kathryn Russo, who heads the drug testing and substance-abuse-management group at law firm Jackson Lewis in Melville, told a U.S. House of Representatives joint subcommittee focused on drugs in the workplace in February.

In a recent interview she said that in the last two years she has received, on average, one to two calls a week from employers about an employee who had overdosed or passed out.

“Those kinds of calls used to be so out of the ordinary a few years ago,” she said.

All local employers should be very concerned about this epidemic, a counseling expert said.

“It’s not just the teenagers, although on Long island our kids are really being impacted terribly,” said Aoifa O’Donnell, chief executive of National EAP, a Hauppauge training and employee-services company. “It’s men in their 40s, women in their 40s. It doesn’t discriminate because it starts with a prescription.”

The Long Island Association, the region’s largest business group, last October co-sponsored a forum to call attention to the impact of opioid abuse on local communities and businesses.

“The opioid epidemic is not only ruining the lives of young people and families on Long Island and throughout the country but also our business community, where millions of dollars are lost in productivity,” said Kevin Law, the group’s president and chief executive.

Capazzi, the construction company president, said that addicted workers disappear for hours or don’t show up at all.

“Once they get that bug, nothing else is important,” he said.

And their loved ones sometimes live in fear around the clock.

“They are sleep-deprived, stressed and frightened,” said Jeffrey Reynolds, president and chief executive of the Family and Children’s Association, a Mineola-based group whose social services include programs for people with substance-abuse disorders. “Family members tell me, ‘I just wait for the phone to ring.’ That’s a rough way to live.”

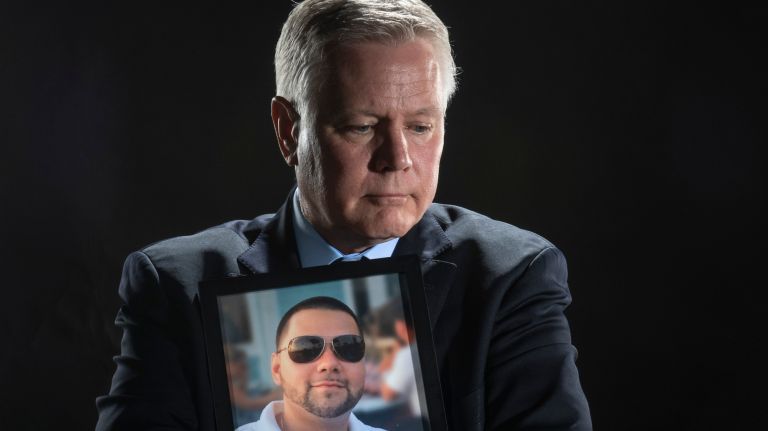

Bill Reitzig, director of business development at Fabco, a Farmingdale storm-water filters company, said that for years he lived in fear of getting such a call about his son Billy, who became addicted to opioids in his teens after being prescribed them to treat an arm broken during a baseball game.

“The worry as a parent . . . is just overwhelming at times,” he said. “It takes away from your focus sometimes at work and a lot of times at home.”

On April 22, 2016, he said, he got the call at work and later learned that his son, who was 25, had died of an apparent heroin overdose.

Yet, many companies and their employees choose to remain silent, rather than intervene early or seek help before a tragedy happens, because of the stigma attached to addiction, experts said.

“We are just now beginning to recognize the effect [of the epidemic] on the business community,” said Jamie Bogenshutz, executive director of the YES Community Counseling Center, a drug-treatment center based in Massapequa

The Long Island Community Foundation, a Melville-based administrative service for charitable donors, is considering co-funding a study to gauge the economic impact of the crisis on Long Island businesses.

We “are engaging business leaders and other stakeholders to join together to fight this drain on our workforce, economy and neighborhoods,” said David Okorn, executive director of the foundation, which co-sponsored the opioid awareness forum.

Reynolds of the Family and Children’s Association said that knowledge of the financial impact would open up more discussion and action on the part of employers.

“I think they would be less in denial if they understood the economic impact this crisis is having on their businesses,” Reynolds said.

Though the crisis has cut across business sectors, employees in certain industries like construction are more vulnerable to opioid abuse because of the high rate of injuries, experts said. The industry is one of the Island’s highest-paying, state Labor Department data show.

Those workers “are more likely to have more work-related accidents and, therefore, . . . are more likely to have been exposed to pain pills,” said Dr. Richard Rosenthal, director of the division of addiction psychiatry at Stony Brook University Medical Center.

As grim as the situation is, some employers are reluctant to talk about it. And their employees are reluctant to admit to an addiction and get help.

“It’s hard enough for families to open up the lines of communication with others about a loved one who is addicted,” said Genevieve Weber Gilmore, an associate professor of counseling at Hofstra University in Hempstead. “So for companies who work every day to maintain their reputation in the community, that stigma also applies.”

As for employees, “A lot of people are afraid they are going to lose their jobs if they get help, not knowing that treatment is confidential,” said Bogenshutz.

Also making the battle difficult on Long Island is that 90 percent of the Island’s 97,400 businesses have fewer than 20 employees. The smaller the company, the less likely it is prepared to offer resources to help employees get treatments, experts said.

“Because they have few employees, they may not have any training for signs and symptoms,” Bogenshutz said.

But it is so important for employers to take the initiative, O’Donnell of National EAP said.

“What we need to do is move the addiction out of the dark and into the light, and the workplace is typically the best way to make that happen,” she said, because a person’s livelihood is at stake.

Some employers like Capazzi and Demetriou said they speak up about the issue and hope to encourage their fellow employers to do the same.

“I do everything I can to mention it, to talk about it,” said Demetriou. “I don’t know the mentality of business owners who don’t want to speak about it.”

It is important for all of Long Island’s companies to go on the offensive in the opioid war, he said: “If we don’t get the coordination and the help from the business community, we will never be successful in the fight.”

Fostering a drug-free workplace

- Recognize workplace problems that may be related to alcohol and other drugs.

- Make sure your medical benefits give employees access to drug treatment.

- Make employees aware of community drug takeback days.

- Host on-site support groups or education sessions.

- Educate employees about drug hotlines.

- Establish a random drug-testing policy.

- Refer employees who have problems with drugs for counseling.

- Protect employee confidentiality.

- Create a culture that is supportive of people in recovery.

Source: Family and Children’s Association and National EAP